It was in February 1918 that the Cross Rip Lightship vanished.

Weir Village and upper Bass River

Six Bridges on Bass River

Idyllic Childhood on Old Cape Cod

The Life and Times of Barney Gould

The herring are coming! The herring are coming!

The herring family includes several species as well as menhaden and shad. Herring are found along the entire east coast of the U.S., and are one of the most abundant fish in the world. These eight to fifteen inch fish return to fresh water each spring to spawn, usually April to early May. Indigenous people said that a certain bush would flower when the herring and shad returned, and that bush is known today as a Shad Bush. Actually, the fish return when the fresh water temperature becomes warmer than the salt.

Herring have played an important role in our history. They’ve been a food source and are great bait for lobster traps. They’ve been used as fertilizer, especially under corn. Up and through the 1800s, much of the catch was used for human consumption, because they kept exceptionally well when salted and smoked. They were then strung on willow or apple sticks and hung in an out-of-the-way place. Today, the roe (eggs) are eaten, either baked until dry or fried in butter. Cape Codders smoked herring almost from the start, but Nova Scotians and people from New Brunswick gained the moniker “herring chokers” by the amount of herring they ate. The Wampanoag supposedly had a secret recipe for smoking herring that people loved.

Locals have regulated herring runs from the beginning, both to ensure everyone was able to get some, as well as to prevent the damming of streams for water power which could prevent herring reaching their fresh water ponds.

Barnstable Patriot, 1852

Yarmouth has had at least seven herring runs in its past. Because Bass River runs were difficult to control as the river was owned jointly with Dennis, in 1849 both towns asked the state legislature to appoint a joint herring committee to control weirs and fishing. Bass River is the beginning of two Yarmouth runs. One went to Laban’s Pond on the Bass River Golf Course. Pesticides and fertilizers ended this run. Another run went from Follins Pond to Mill Pond up Hamblin Brook to Miss Thatcher’s Pond near Seminole Drive. This run was quite profitable, selling for $710 to Nathan Grush in 1880. In 1883, it produced the second most herring in the state : 280,797. However, by 1914, the highest price paid for any herring grant on Bass River was just $31.

A third run went past West Yarmouth’s Baxter Mill up into the Mill Pond (another one) and on to Little Sandy Pond, now town recreation land. A fourth went up Mill Creek, then under Route 28 near where the 1750 house used to stand, and on through the cranberry bogs and on to Jabez Ned’s Pond just south of Buck Island Road.

Baxter Mill

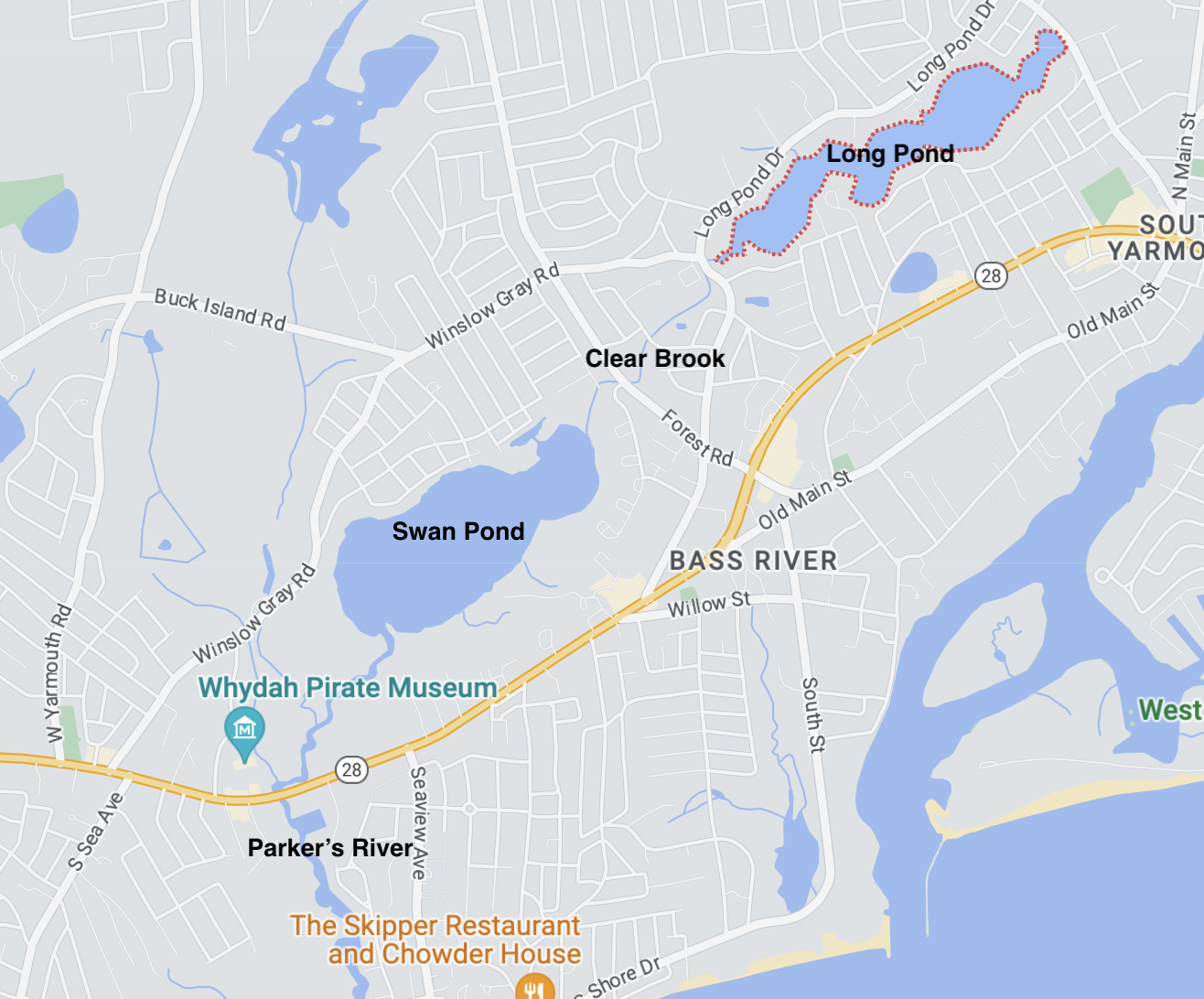

A fifth went up Parker’s River to Swan Pond and then up Clear Brook under what is now Forest Road to Long Pond. In the long term, this was probably the most profitable in the town. The state legislature enabled it in 1843 when it allowed the owners to open an outlet from Long Pond to Swan Pond. This was a half mile of digging! It is still an active run.

The sixth and seventh runs both went up Chase Garden Creek on the northside and into White’s Brook. One then went into Matthews Pond on Bass River Rod and Gun Club property, while the other continued under Route 6A to a little pond behind the town pumping station building on Union Street.

Three runs in Yarmouth are still active. The biggest is the Clear Brook Run. Under the direction of the Yarmouth Department of Natural Resources, the brook was dug out in 2009 where it was too shallow and a culvert was removed at the end of Clear Brook Road. A bridge was built over the stream. Americorps helped improve that run in 2009. In 2011, the Cape Cod Salties fishing organization helped clean the whole brook and did a wonderful job. Herring can be seen from the bridge at the end of Clear Brook Road, and from the walkway on Forest Road. Before the improvements, some herring made it through to Long Pond, but now far more are making their spawning journey.

The fish ladder beside the Baxter Mill on Route 28 is still active. Herring used to swim through Mill Pond and up to Little Sandy Pond, but that stream is now blocked. The herring spawn in Mill Pond and return to the ocean down Mill River.

In the 1960s, the Bass River Rod and Gun Club built a fish ladder into Matthews Pond to allow the herring to spawn there. The state stocked it for several years until the herring returned on their own. The club, with the help of groups such as the Cape Cod Salties, maintains the run.

So, when the Shad Bush flowers this spring, look for herring right here in Yarmouth. Remember the state-wide ban on taking herring, so only look, though local indigenous people do retain the right to harvest. The osprey and seagulls know when they arrive - they are part of the welcoming committee!

Shad bush

Excerpted from an article by Duncan Oliver

The Pirate’s Girl - Yarmouth’s? Maria Hallett

2017 marked the 300th anniversary of the wreck of the pirate ship Whydah off the coast of Wellfleet. Sam Bellamy was the captain who died in that wreck, and his girlfriend Maria Hallett witnessed the tragedy.

The late Yarmouth and HSOY historian Haynes Mahoney once remarked that he had seen a document which mentioned that Bellamy’s girlfriend Maria Hallett was a tavern maid at the Old Yarmouth Inn before she moved to Eastham. Sadly he never revealed the source of that information and it remains a mystery. Was she?

Author Kathleen Brunelle, in her book, “Bellamy’s Bride – The Search for Maria Hallett of Cape Cod,” writes that in some legends Maria hailed from Yarmouth but later settled in Eastham though she wasn’t able to give definitive information. Maria’s birth doesn’t appear in any of the local town vital records. Yarmouth likes to claim her; little has happened on Cape Cod that doesn’t have some Yarmouth connection!

Maria’s age has never been ascertained with certainty. Most of the legends say she was 15 or 16 at the time Sam Bellamy met her in Eastham in 1715. A girl of 15 could be married then as the age of consent in 1715 was 11, based on the 1642 Capital Laws of New England. Maria’s probable Yarmouth ancestor, her presumed grandmother Anne Bearse, married at age 14.

Location of the Whydah wreck off Wellfleet.

Maria is said to have met Sam Bellamy at the Higgins Tavern in Eastham, a place where young girls would not ordinarily be unless, of course, Maria had worked at another tavern earlier – perhaps the tavern in Yarmouth.

We all know the story – a pretty young girl, unmarried and pregnant, sees her beau leave on an expedition to the West Indies. Being pregnant before marriage wasn’t a terribly unusual situation in the early 1700s. More than one in four women were already expecting a child at the time of their marriage. Maria’s baby died shortly after being born in a barn and some believed she killed the child. The town fathers imprisoned her and after she escaped several times they eventually banned her from town. She moved to Wellfleet and became a recluse in what is now the Marconi beach area. That land is still called the Goody Hallett Meadow.

Was she bitter about Sam leaving her and dying? Legends take two directions on this. In one, she pines for Bellamy and is devastated by his shipwreck near her shack. In the other, she blames him and puts a curse on his boat, causing it to wreck. In this version Maria has become a witch, called Goody Hallett, able to do such things.

Since then, many, many authors have given their own spin on the story, with Kathleen Brunelle’s book covering virtually all of the variations in the Maria Goody Hallett legend. Wherever Maria hailed from, her legend lives on.

*********

To learn about a very real pirate’s lady, join us on April 19th at 7:00 pm at the South Yarmouth Library when local author Daphne Geanacopoulos will tell us about her research into and subsequent bestselling book about Sarah Kidd, the wife of the pirate Captain William Kidd. Not legend, Sarah was a very real person and a very interesting one!

Victorian Feminist Meets Yarmouth Sea Captain

In the heady days of the burgeoning gold rush to California, two unlikely shipmates found themselves under way in the old packet, Angelique, which departed New York in April, 1849 for San Francisco.

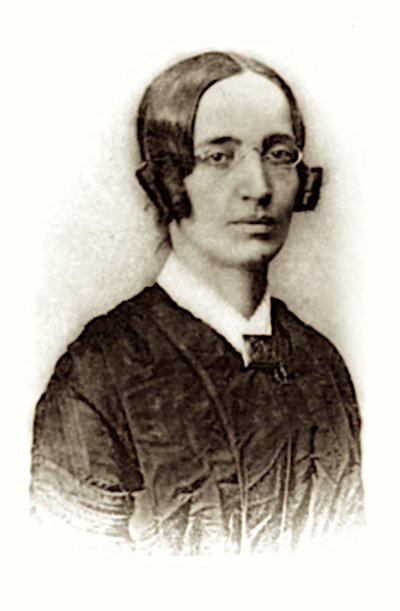

Eliza Farnham, published author and former matron of the female section of Sing Sing Prison, was not going for gold but “to bring refinement to that disorderly city.” Sturgis Crowell, from West Yarmouth, was making the voyage as first mate but hoping one day to get a ship of his own.

According to the book Eliza wrote about her California adventures, both of them suffered under the irascible command of Captain Phineas Windsor.

Eliza’s original intent was to claim a tract of land near Santa Cruz left to her by her adventurous husband who had traveled to California several years earlier and died there in 1848. But true to her feminist idealism she developed a plan to organize a group of well recommended marriageable women who would “bring their kindly cares and powers” to that rough hewn society of gold miners. In the end only 2 accompanied her.

Sturgis Crowell, born in West Yarmouth, had gone to sea at age 10 as cook on a coasting vessel. And, now at age 27, was making his first voyage as first mate on a full rigged ship, rounding Cape Horn to San Francisco. While his association with Mrs. Farnham was limited to this voyage, it must have been an unsettling experience for both of them. The formidable lady was soon involved in a raging feud with Captain Windsor, whom, she said “never named women but to deprecate them in the coarsest terms.”

The captain suspected the lady had inspired a rebellion among the 22 passengers, forcing him to make a stop at St. Catherine’s to give them a rest and replace “the bad water” on the ship about which all complained. Their relationship was further inflamed when Eliza’s nursemaid began an affair with the ship’s purser and the captain did nothing about it. Ultimately they rounded the Horn and put in to Valparaiso, Chili, where the girl married the purser, and Eliza recruited a young Chilean woman as servant. Evidently the Captain had enough of Mrs. Farnham, and while she went back ashore to get the necessary passport for her new servant, Captain Windsor raised sail and put to sea, taking her companion and her children.

Valparaiso

Through all these tribulations, she wrote kindly of first mate Crowell from Yarmouth, “whose good nature and kindness to the passengers, especially to the females and children, had caused him much difficulty with the captain...”

A lone woman, friendless and penniless in a foreign port was in dire circumstances -- even for the resilient Eliza. Eventually with the help of the American consul she found passage to San Francisco, arriving a month later. There she was soon reunited with her friend and children.

Eliza soon left San Francisco, found her husband’s property, and with her own hands and help from her friend Miss Sampson and later Georgianna Bruce, rebuilt the house and developed a farm. Her companions returned home after two years with sufficient fortune to keep themselves comfortable for the rest of their lives. Eliza did not say how they gained such wealth. Eliza married in 1852, and developed a successful agricultural business but she divorced in 1856, and returned to New York City, where she published several books based on her experiences, and helped destitute women to find new homes in California.

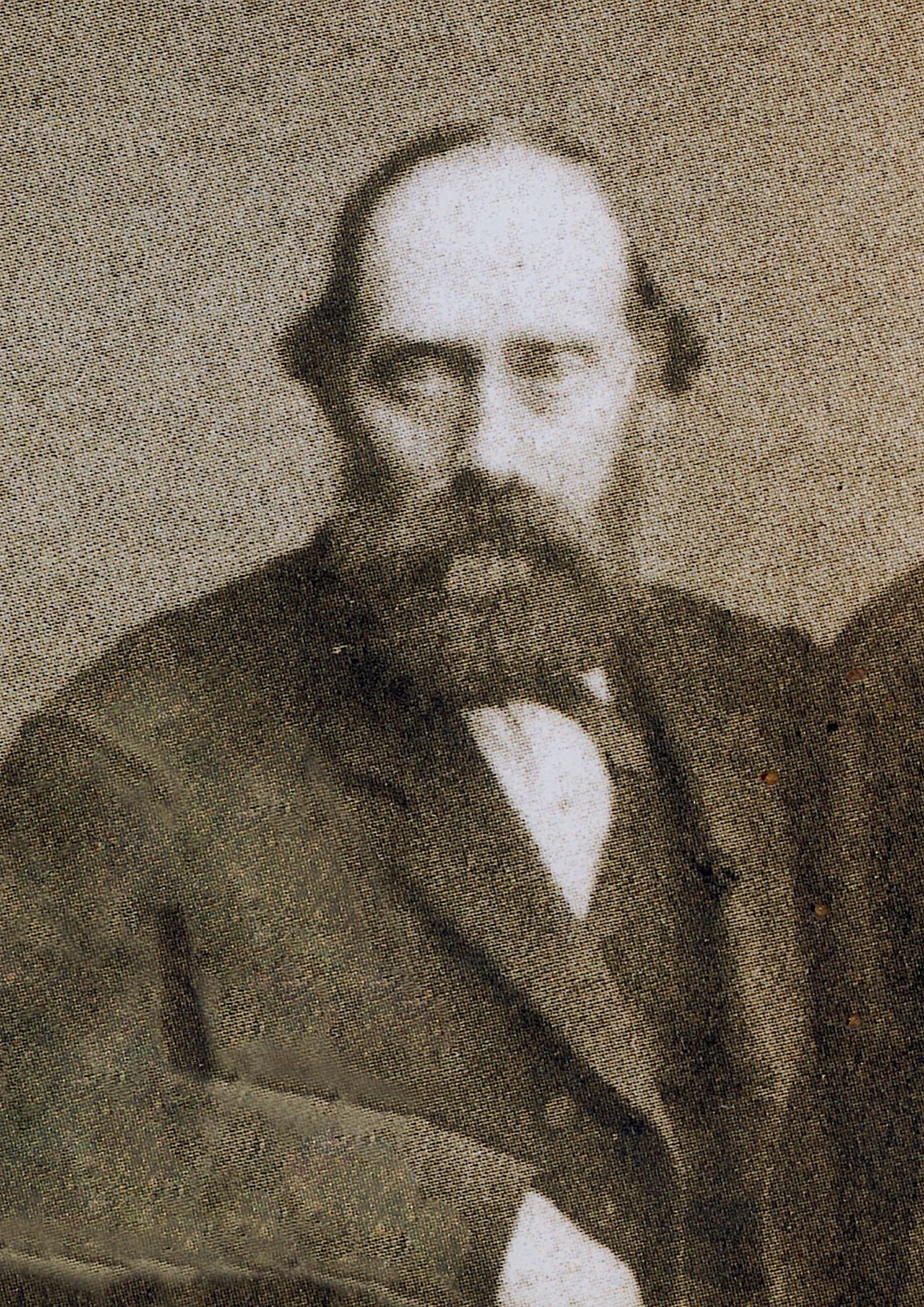

Meanwhile Sturgis Crowell continued as first mate in various vessels until 1861 when he was finally made captain of the clipper, Boston Light, departing New York for San Francisco, May 23, 1861. After a month unloading and gathering a new cargo, he was off to Honolulu, Mauritius and Calcutta where he received a message from the owners to sell the ship. Instead, Crowell sailed with a cargo of rice to Hong Kong, and there sold the vessel in January, 1863 at a price which pleased the owners.

Captain Crowell retired to his home in South Yarmouth on Old Main Street in 1873, nearly 10 years after Eliza Farnham died of tuberculosis in New York. Honored and respected, Crowell lived some 40 years in South Yarmouth until he died at age 89.

Excerpted from an article by Haynes Mahoney

Yarmouth's Miss Mary Thacher

Benjamin Boardley of Mashpee - the former slave who invented a Navy steam engine

Benjamin Boardley (sometimes called Bradley) was born a slave to a woman named Flora in Anne Arundel, Maryland in March of 1836. Their owner was John T. Hammond.

Benjamin likely learned to read from or with his master's children. As a teenager, Boardley worked at a printing office where he showed ingenuity and mechanical prowess. He built a steam engine out of a gun barrel, pewter, round steel, and other various materials. His master was so impressed, he found him a job as a helper at the Naval Academy at Annapolis. According to the African Repository of 1859, he was paid in full for his work, but the money he had made went directly to his master, who allowed Boardley to keep five dollars a month for himself.

US Naval Academy, 1860s

Professors at the Naval Academy were fascinated with him and a Professor Hopkins wrote that he would set up experiments rapidly, was a quick learner, and the professor noticed that "he always looks for the scientific law by which things act." Hopkins's children taught Boardley mathematics such as arithmetic, algebra and geometry.

During his time at the Naval Academy, Boardley built a steam engine and sold it to a midshipmen. With the money he earned from selling it he designed a steam engine large enough to run the first mechanical sloop of war that could exceed 16 knots an hour. He sold this model engine to a fellow classmate from the Naval Academy and then used the proceeds to design a steam-powered warship. Because he was a slave, Boardley was never allowed to receive a patent for the engine but he was able to sell it. He used the profits, plus the money he earned at the Naval Academy, to obtain his freedom at a cost of $1,000. Boardley was manumitted from his owner, John T. Hammond, on September 30, 1859.

During the Civil War, the U.S. Naval Academy relocated to Fort Adams in Newport, Rhode Island. Boardley was employed there where, under the supervision of Professor A.W. Smith, he continued his work on constructing small steam engines, improved his excellent mechanical skills and worked as an instructor.

He married in Boston in 1864 and by 1865 Boardley was living in Mashpee where records say he was a merchant.

In the 1880s Boardley worked with Herbert Crosby to build a 35’ steam powered boat called Quichatasett, for use on Wakeby Pond, which was launched in 1891. His steam engine drove two side wheels, powering the boat around the lake, popular with fishermen and tourists visiting the area. President Grover Cleveland rode in the vessel with his fishing buddies to go to their favorite sections of the lake. Around this time the steamship was renamed Ruth, likely to honor Cleveland’s daughter. Boardley and his son William, who lived in a cottage on the shore, operated the boat on the lake for about 30 years.

The Quichatasett on Wakeby Pond.

Benjamin Boardley died in 1904, leaving behind his second wife Gertrude and several children. This highly accomplished man was buried in Mashpee Town Cemetery.

Based on an article by Dr. Michael Pregot, with additional research and text.

Keeping it cold

This weekend’s weather reminded us that ice harvesting was big business before refrigeration and local ice houses would have welcomed those freezing temperatures.

From the time of the early settlers on Cape Cod, on up to the nineteen-fifties, ice was harvested from lakes and ponds. In the seventeenth century locals would head to the nearest fresh water source, and by whatever means possible, usually with just an axe, chop what they needed.

Over time methods and tools were developed to maximize the harvest, allowing ice to become a commercial commodity. In order to have ice available past the coldest months, ice houses were built for storage and preservation. They were constructed with double walls insulated by salt hay, sea weed, sawdust or pine needles. The roofs were often painted white to reflect the heat of the sun. The floor was covered in sand and the ice stacked with sawdust between each layer for insulation and ease of separation. Dampness being the enemy of ice, they were built in the open, away from trees and greenery.

Usher’s Ice House at the west end of Dennis Pond

By the mid-nineteenth century almost every town and village had at least one commercial harvesting operation and those without regular jobs were happy for the extra work in winter. Yarmouth was no exception, and in fact had several at the same time. They were located at Dennis Pond, Sandy Pond, Whites Brook, Mathews Pond, James Pond and Long Pond. With over three hundred and fifty lakes and ponds on Cape Cod, there was no shortage of the resource during the cold winter months.

One common method of ice cutting was the use of a horse pulled, plow-like combination saw blade and guide. A straight line was marked on the ice and a groove was cut into the line. The guide was placed in the groove and the parallel saw blade cut the blocks. This allowed the “cakes,” to be cut to equal size. After several passes the cuts got deeper leaving less ice for the final cut by hand saws. Many of the tools used for this operation resembled those used by loggers, such as long saws for cutting, thongs and pikes to lift the blocks and slide them to the ice house.

Ice harvesting on Sandy Pond in West Yarmouth.

Ice harvesting was not without dangers; it was not uncommon for man or beast to fall into the frigid water. They had to be pulled out and dried off quickly to prevent hypothermia. It took keen senses and experience to know how much to cut while keeping the ice sheet safe. Sam Thacher recalled falling in and running all the way home from Dennis Pond to near the Yarmouth Port Playground before he froze, to get dry clothes.

A horse and wagon, a man with a strong back, and a few basic tools were all that was required to deliver ice. The ice man’s tool kit comprised of an ice pick, scraper, tongs and a shoulder pad. Delivering ice was hard work, especially in an urban setting due to the stairs and the number of customers in each multi-level dwelling. The iceman’s day started in the pre-dawn hours and ended twelve-to-fourteen hours later.

Usher’s Dennis Pond Ice in Yarmouth Port

As small towns and urban centers grew, it was not easy for the iceman to memorize each customer and what their needs were. As with most things when technology had not yet invaded our lives, a simple solution was put in place. A card that indicated how much ice was needed was displayed in a window facing the street. The card had amounts printed on its four sides, simply by turning the card so that the desired amount was at the top, the iceman was able to cut what the customer needed. This method was also used for coal, and later for oil deliveries.

Example of an ice delivery card.

The Bay State Freezer Company, started in 1916, was located in Yarmouth Port on Wharf Lane. It was a large commercial ice making business that catered mostly to the fishing industry. They owned a dock that enabled the fishing boats to load directly from the plant. They also offered storage facilities to keep the catch fresh prior to distribution. The development of frozen foods and on-board vessel ice making led to the operation closing in 1921.

Bay State Freezer Company in 1919, located at 111 Wharf Lane, Yarmouth Port

Fast forward to current times, ice is at our fingertips. No longer do we need to scrape or chip ice, it’s readily available in convenient cubes. Need some for a quick drink, it’s on the refrigerator door. Need some for a pitcher full, it’s in the freezer in refillable trays. Need some for a party, there’s a big chest full of bagged ice cubes out in front of the nearest grocery store or gas station.

The memory of ice harvests, the joy of a chunk of ice on a hot summer day, and the old kitchen ice box, lingers among the cobwebs in the minds of those of us of who are of a certain age. With age comes the knowledge that there’s more to life than convenience.

Kids grabbing ice chunks on a hot summer day - considered a real treat.

excerpted from an article by Frank Tardo

Flying Machines in Yarmouth

The first Cape Cod non-military landing field was in West Yarmouth when Aero Service of Framingham opened a field on July 5, 1920. It was located off of South Sea Avenue on the shore of Lewis Bay, advertised as being just a six minute walk from the Hotel Englewood. It was to be a summer field for passenger flights, instruction, aerial photography, and advertising. The plane arrived in Yarmouth after a “record” (for speed) 61 minute flight from Framingham. The pilot, Lt. George Hall, was advertised as being experienced but in fact he had earned his wings just two years earlier at Fort Worth, Texas and had flown with the Canadian Royal Air Force. The mechanic, C. Gould Weld, was a “mechanical engineer of repute on aeronautical motors.”

Aero Service’s airplane in West Yarmouth

Aero Service lasted only ten days. “On Wednesday afternoon the plane came abruptly to the ground from a great height. … A great crowd took up the search for its landing place. … After hours of searching the plane was located in the mud at Halfway Pond and its occupants still strapped to the machine, and that death had claimed them where they reached the ground.”

Another photo found in our archives of a bi-plane noted that it landed in the Englewood section and also later crashed. Whether it was at the airfield briefly operated by Aero Service isn’t known. There was a golf course near Englewood, owned by Simeon P. Lewis, and that would have been another likely area to land.

Civilian seaplanes came to the Cape and used Bass River as one of their landing places. Bass River was an ideal landing spot, being somewhat sheltered from high waves. Charles Henry Davis, one of Yarmouth’s more famous citizens, first brought his Curtis seaplane to his house alongside Bass River on July 17, 1922. A South Yarmouth reporter said the event caused considerable excitement as “it was the first airship to bring a passenger to our little community.” The Cape villages of the time considered themselves separate entities, thus the notation that it was a first for South Yarmouth, as opposed to West Yarmouth. Davis liked the speed which seaplanes afforded. He used them at least occasionally to commute between New York and South Yarmouth. Below is Charles Henry Davis, his pilot, and his Curtis Flying Boat in 1919.

1919

Davis was well known. A senior partner of a consulting engineering firm and a brilliant inventor, he designed the first skyscraper 30 stories high, the first high speed streamlined electric railroad train, fireproof vertical filing units, and color movie tones. He never took out patents, preferring to give them to the public. Looking at transportation in the future, and planning for it, Davis started the National Highways Association in 1911. The improvements he recommended were flat roads, stop and go signals, and banked curves. He published, at his own expense, series of road maps, many of them drawn at his home “Seven Chimneys” on River Street in South Yarmouth. The rotary at the intersection of River and Pleasant streets was supposedly the first rotary in America.

A second seaplane that landed on Bass River was owned by Simonds Saw and Steel of Fitchburg. When visiting Frank and Gloria Sargent, living at the corner of Homer Avenue and Pleasant Street, it would land on Bass River and taxi up to the Sargent’s beach and park there. The pilot’s name was Joe Fluet.

The dirigible Graf Zeppelin was spotted on November 1st 1928 as it was returning to Europe after its maiden voyage to America. Mr. and Mrs. Winslow Thacher went out on West Yarmouth’s Great Island in Lewis Bay to witness it early in the morning. Nelson Bradford said he was awakened by the vibration of his house as it passed over. The Zeppelin flew at 600 feet and 80 mph. It cost $700 for a ticket – about $14,000 today - an amount only the very wealthy could afford in 1937.

Graf Zeppelin

Another major aeronautical incident occurred the evening of June 17, 1979. Air New England flight 248 crashed into the woods at Camp Greenough with eight passengers, and two pilots on board. Coming from LaGuardia Airport in New York, the plane was on approach to Barnstable airport in dense fog just before 11 p.m. Only the captain, George Parmenter, died in the crash. Suzanne Mourad, one of the passengers, stumbled through the woods to Route 6 where she flagged down a vehicle then later announced at Barnstable Airport that Flight 248 had crashed. Another passenger, Robert Sabbag, wrote a book about the crash, all of those on board, and the first responders in Down Around Midnight.

There have been complaints about noise caused by planes approaching Barnstable airport as they pass over Yarmouth. The Northeast Yellowbirds in the 1960s were very loud, and there were even complaints about sonic booms from the Concorde when it flew over Cape Cod coming and going to New York. Those complaints lasted from 1976 until 2003 when the Concorde stopped flying but air traffic continues to this day, bringing both tourists and residents from afar to our tiny peninsula.

Excerpted from an article by Duncan Oliver.

Yarmouth’s Guido Perera, right.

The first trip by car to Provincetown

The arrival of the first automobiles on America’s roads in the early twentieth century fundamentally changed everyday life on Cape Cod. For residents and tourists alike, motor vehicles opened a path to faster, easier and more pleasant journeys than were previously possible by ship, coach or train.

In 1901 a first ‘around-the-Cape’ trip was accomplished by two friends aboard a red, steam-powered Stanley Steamer car. The automobile owner was Charles Lincoln Ayling, a Boston resident who spent summers in Centerville. His was one of just 600 cars registered in Massachusetts in 1901. He and William Morgan Butler left at dawn and returned home by dusk next day. That 36 hour dash led north to Old Kings’ Highway (now Route 6A), northeast to Provincetown then back along what is now Route 28.

Charles Ayling as a young, then older man

Subsequently, Ayling was to claim (with the backing of others) that his was the first-ever round trip by car to span the full length of the Cape. He later would achieve success as businessman and philanthropist, well-known on the Cape as a benefactor of Cape Cod Hospital, the Centerville Historical Museum, and a founder of the Hyannis Airport, among other things.

The Main Streets of Yarmouth Port, Dennis, Brewster and other villages were described at the time as well-curbed, incorporating lengthy strips of macadamized surfaces while being shaded by fine trees. These roads offered striking views of quaint houses, neat farms, cranberry bogs, marshlands and pristine local waters. However, beyond downtown areas roads typically were unpaved and blighted by deep ruts engraved into their surfaces. These had been formed by grinding of the wheels of the endless flow of carts, wagons and coaches. Unfortunately, these permanent ruts or tracks were some 6-to-12 inches further apart than the standard gage adopted for automobiles. This caused a problem for Ayling’s companion who was forced to spend hours in discomfort, perched at an awkward angle with his head way above that of the driver!

Nevertheless, the 1901 vintage ‘Steamer’ made a 15 mph average and at times hit 30 mph even on rough roads. The vehicle was a big hit among early car owners, who on account of its odd shape, affectionately named it ‘The Flying Teapot.’ It had a gas-fueled boiler under the front seat to generate steam, then transferred energy to the rear axle to power the car. The chassis was wood.

But the ‘Steamer’ could also be a travelers’ nightmare, especially on roads that were rutted, winding, hilly and plagued by sand build-up. So Ayling’s progress was punctuated by lots of slowdowns and even dead stops.

The greater challenge came upon reaching the Outer Cape where roads had been labeled by a travel guide as ‘worst in State.’ Old maps show that these roads faded into a spider’s web of tangled, narrow trails. At this time auto service providers on the Outer Cape were pretty much non-existent.

Ironically, progress in other means of transport had exacerbated the wretched state of Outer Cape roads. Steam ships gave the region access to the outside world by providing reliable packet and ferry services and the Cape Cod Railroad had stretched all the way to P-town by 1873. Both advances undermined the incentive to improve Outer Cape roads and left the area poorly prepared for the emergence of autos.

A hardship for ‘Steamers’ was an insatiable thirst for water, necessitating many refills once initial supplies were gone. Luckily, drinking troughs for horses existed in most villages, making it easy for car drivers to refill their radiators.

Obtaining gas was another hurdle, so long-distance drivers had either to carry gas cans or bargain for fuel from local businesses (e.g. painters, hardware stores) that held stocks for their own use and tires of early cars were troublesome due to their smooth, no-tread design. Ayling was forced to make time-consuming tire changes and patch-fixes several times during the trip.

Another obstacle was that at various points Ayling found himself stalled by a curious, excited yet fearful crowd of onlookers, many of whom had never before seen a ‘horseless carriage.’ He also found himself blocked at times by horse-drawn vehicles passing from both directions. This required one of the men to get out and to cajole nervous horses on their way.

Despite everything, at dusk some 12 hours after his departure, Ayling arrived in P-town only to be greeted by the Town Crier. Bearing a flag and clanging a bell, this official guided his visitors through an enthusiastic throng and on to Gifford House, a local lodging place.

But the proprietor had one final surprise for Ayling: he was worried that his guest’s ‘steam dragon’ might be too great a fire hazard for it to be parked in the inn’s courtyard. This decision forced our travelers to scurry around and find an abandoned barn as the haven for the little red ‘Steamer’ for the night.

Gifford House

Excerpted from an article by HSOY member Bob Leaversuch

Do you love Yarmouth history? Become a member! The first year is free.

1902 Stanley Steamer.

Cape Cod Salt Marshes - asset or swamp?

Yarmouth’s first European settler, Stephen Hopkins, came to our town in 1638 because of the salt marshes. He wanted to winter his cattle here because salt marsh hay was ideal feed. The Plymouth fathers allowed him to build a house in Yarmouth but told him he couldn’t stay here permanently.

Marshes were valued as property. Property lines were cut in the marsh by removing the top layer of peat. These straight ditches are still evident. Throughout the 19th century, property that was sold made sure the deed included marsh, and the marsh size was indicated by the number of tons of hay it produced each year.

Early farmers cut marsh hay for their animals and used it for many other things, such as helping to store ice during warmer weather and stuffing mattresses. The Sandwich Glass Company shipped their glass protected by salt marsh hay. Old hay and seaweed packed around foundations kept houses less drafty in winter. Cows fed salt marsh hay often produced salty milk, something old timers vividly remembered. They said you could tell immediately when a farmer switched the feed later in the winter when the regular hay ran out.

Cutting the hay using scythes was done late in the season, usually in September after other hay had been cut. It was stored on staddles. A staddle is a series of wooden pilings in the marsh that allowed hay to be piled above high water. Early in the 19th century, there were more than 1200 staddles in the Barnstable marsh.

Harvesting salt marsh hay in the Great Marshes, West Barnstable

Hay barges were used to collect hay and brought it to staddles or to shore. The barges could be rowed, poled or sailed. Horses gathering hay wore bog boots (wide wooden shoes attached to their hooves) like snowshoes.

Hay was usually removed from staddles in January, after the marshes had frozen. 1880 was a warm winter and farmers complained they couldn’t get their horses onto the marshes until near the end of the winter. Leaving hay on staddles during winter storms meant some were destroyed. Thirty staddles were lost in West Barnstable in a January 1886 storm. Many staddles were lost during the 1898 “Portland” storm and most weren’t rebuilt.

Locals, especially the poorer ones, burned marsh peat for fuel after wood became scarce. Peat could extend down 20 feet deep in places. They cut the peat with a shovel, just like in Ireland. It was stacked and air-dried.

Even the Massachusetts National Guard liked the marshes. In 1922, the Guard used Sandwich marshes for artillery practice, preventing farmers from accessing their land.

Soldiers boarding the train in West Barnstable after training on Sandy Neck and in the marsh.

In the 1930s, mosquito control cut drainage ditches in the marsh, to drain puddles and low spots that remained at low tide. These allowed minnows and other fish to reach and eat the mosquito larvae. Boundary ditches and mosquito control ditches are easy to tell apart. Mosquito control ditches stop when they reach a stream, whereas lot lines continue through. You can easily see this looking from the Bass Hole boardwalk.

Straight ditches cut into the marsh at Bass Hole.

Mosquito control took place as the Cape turned toward a tourist economy. The dreaded greenhead, a type of horse fly, was another tourist chaser who inhabited the marshes. During June, July and into August, these nasty females (yes, only the females bite) chased people from the beaches.

Local lore says that the very high tides caused by the full moon late in July mark the end of the greenhead season by drowning the larvae. The environmentally safe blue box traps are the real solution. A single box can trap over 30,000 flies in a season and the state puts out more than 900 traps on Cape Cod. The flies, attracted to the color, fly up underneath, enter the trap, and cannot find their way out. The mosquito control ditches actually helped the greenheads because they kept water levels down. Control by using DDT had a disastrous impact on the environment.

The mosquito and boundary ditches are one of the causes of the decline of our salt marshes. When cordgrass started to disappear, at first scientists were mystified as to the cause. Drought, climate change, and other items were blamed, but our native purple crab was eventually identified as a major culprit. To quote scientists, “the mosquito ditches … facilitated corridors to low marsh cordgrasses. As striped bass and blue crabs were being overfished, purple crabs experienced a fourfold increase in population. Suddenly these corridors to the cordgrasses became superhighways for hungry purple crabs to burrow while eating too much eelgrass, exposing the peat and turning it to mud so the marsh grasses can’t regenerate. More than 80% of the Cape’s marshes are retreating.

An unlikely hero is coming to the marshes’ rescue. A highly invasive non-native European green crab that perhaps came here on vessels from Europe, finds that purple crabs are “delicious.” Some scientists now say “Our results show, that despite previous evidence of negative impacts on native species, the European green crab is well suited to accelerate the recovery of heavily degraded salt marsh ecosystems in New England.” Is there a down side? Probably, but the marshes may return to a healthier state than they have been.

Even in the last 50 years some Yarmouth developers have tried to remove marshes. The Hyannis Park Civic Association has helped prevent two such projects from happening. A proposal in 1963 attempted to dredge out an 80 foot lagoon on the eastern side of Hyannis Park and fill three acres of marsh with the sand, allowing 15 more house lots. It wasn’t allowed. In 1993, an ambitious plan called Discovery Harbor was proposed, dredging out much of the marsh as well as the cranberry bog and making a large marina along Bayview Street. The plan included berths for cruise ships, a Coast Guard Station, and a large marina. This was to be on land owned by Cape Cod Hospital. It failed as well.

So, when you complain that the Yarmouth selectmen gave Dennis all the good beaches when the two towns split in 1793, remember - at that time there were no tourists, people didn’t want to live near the beach, and the salt marsh hay was far more valuable than sand. For more than 100 years, Yarmouth thought that it got the best deal!

Excerpted from an article by Duncan Oliver.

The Listening Posts

Let's go to the Drive-in!

Yarmouth's Very Own Theater

The Great October Gale of 1841

Being in the thick of the Atlantic hurricane season, it’s a good time to look at the one storm which had the greatest impact on Cape Cod history. If you asked twenty Cape Codders which storm this was, there’s a very good chance that they wouldn’t choose the Great October Gale of 1841. The 1938 Hurricane, the twin Hurricanes Carol and Edna of 1954 arriving just 11 days apart, or Hurricane Bob might be mentioned. Reaching back to the 19th century, the Blizzard of 1888 even could be an answer.

However, Cape Cod was rebuilt after each of these massive storms and continued on. Only one storm, the Great October Gale of 1841, changed the course of Cape Cod’s economic history. Today, this storm would have been classified as a large hurricane, and its direct fury as a storm lasted four days. Its impact on the Cape’s economy is still felt today.

Lasting from October 2-6, the outer beach was strewn with the parts of 50 wrecks and 100 bodies were taken up and buried. Cape fishing fleets were decimated by the storm. The Cape fleet was at George’s Bank fishing for mackerel at that time, and was destroyed as the storm hit both the Cape and George’s Bank. Truro lost 57 men and seven vessels; Dennis lost 22 men, and Yarmouth lost 10 men - a tragic loss for those small tight-knit communities. On the south side of the Cape, Falmouth lost as many men as all of the north side. Fishing fleets never recovered from the damage and there was neither money nor manpower to rebuild the fleet. It was shortly after this storm that fishing weirs began to appear along beaches and inlets of Cape Cod. The fish weirs were a less expensive method of fishing, but were far less successful, and never replaced the fleets. Only Provincetown’s fleet was rebuilt to its former size.

Places where fish weirs had been in use before the storm were decimated by it. Follins Pond at the northerly end of Bass River silted in so badly that fishing on that salt water pond could no longer remain a viable economic force. The Weir Village section of Yarmouth, which bordered Follins Pond and Mill Pond, became a ghost town. Houses were even moved to other sections of the town after the storm. Today, Weir Road in Yarmouth gives few clues to the former active fishing village of the area.

Chase Garden Creek took in so much silt that it lost its tidal force and ability to float schooners down to Bass Hole. From the October Gale on, the tide never came into Bass Hole as it had. Prior to 1841, it was Chase Garden River. While the old-timers continued to call it that, within 25 years of the storm, maps had started referring to it as a creek. The two ropeworks in Yarmouth, one by the Yarmouth Port playground and another along Bass River, stopped production by 1850, and perhaps a few years earlier.

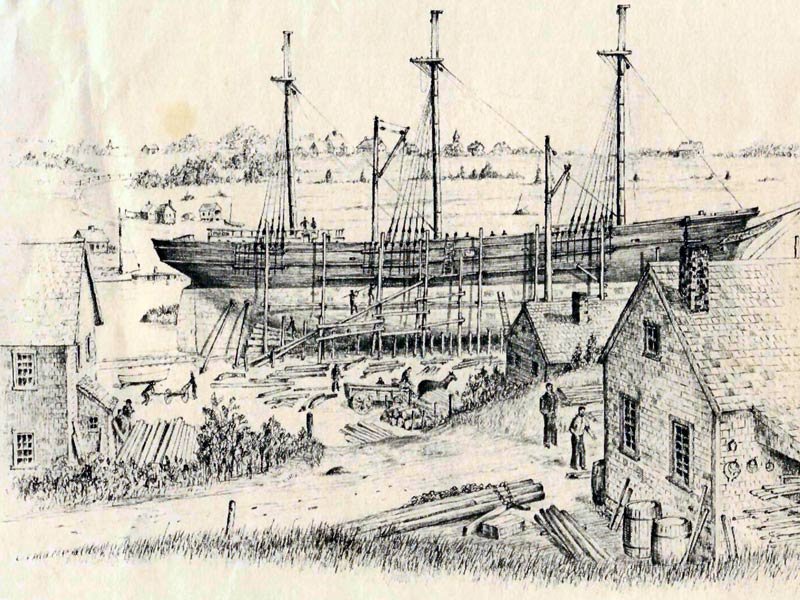

The only exception to the loss of shipbuilding was at the Shiverick shipyard in East Dennis. Starting in 1848 and lasting until 1863, Shiverick built some of the best clipper ships ever to sail.

Image from Dennis Historical Society.

Saltworks, once so common around the Cape, took an incredible hit. With fewer fishing vessels to buy their salt, and the cheapness of imported salt, many saltworks were never rebuilt after the October Gale of 1841. Some of the wood from these saltworks was used in construction. One of the more notable was the Kelley Chapel, now on the Historical Society’s grounds.

Saltworks along Bass River.

Few storms have hit at a worse economic time. Starting in the decade after the storm, the Cape Cod’s population experienced a decline that wasn’t reversed until the century ended. Only the rise of tourism, which began after the Civil War, brought the economy of Cape Cod some new hope.

The Nobscusset Hotel, courtesy of the Dennis Historical Society.

Excerpted from an article by Duncan Oliver.

For more details about the October Gale, watch this interesting video, courtesy of Friends of Ancient Cemetery.

Mill Lane, the oldest road in Yarmouth

Mill Lane, the oldest verified way in Yarmouth, began its existence in 1638 as an oxen path. It was the first settled part of the town of Yarmouth, extending east to Chase Garden marshes.

Mill Pond in the 1860s.

Long before the 1630s, when the first English settlers arrived in Yarmouth, many generations of indigenous peoples made their home here. The area was known to them as “Mattakeese.” They lived in simple structures called a wetu, domed dwellings made of bent red cedar saplings and covered with rush matting and bark with smoke holes and doorways [you can visit a wetu next to our Yarmouth Port Nature Trails]. Game was plentiful and was supplemented with shellfish and fish caught in traps and weirs. By 1640 Mattakeese had been renamed Yarmouth by the settlers after a seaside town in their native England.

Stephen Hopkins of the Mayflower was the first settler in the Mill Pond area. He was allowed to come here from Plymouth and take advantage of the salt marsh lands to feed the hay to his cattle.

At the end of 1642 Andrew Hallet purchased Stephen Hopkins’ house from Giles Hopkins, his son. It was located near the corner of what is now Mill Lane and Old King’s Highway and was a one room cabin made of hand-sawn boards, cracks daubed with clay, a thatched roof, a stone chimney and oiled paper windows. Within a few years he acquired some 300 more acres in the area.

Nathan Matthews on the bridge, next to the old mill, late 1800s.

The first mill, from which the pond and creek got its name, was mentioned in town records as early as 1647 - the tidal gristmill located on the left side of Mill Pond, owned and operated by Andrew Hallet. He later sold a portion of his land, along with the gristmill, to John Gorham who ran a tannery on the right hand side of the pond. The mill business was vital to the community and millers were exempt from military service.

48 Mill Lane

It is believed that Captain Ansel Hallet, born in Yarmouth in 1770, built the Federal style home at 48 Mill Lane shortly after his marriage to Anna Eldridge in 1798, though the house could be older. He was a pioneer in establishing the packet ship lines between Yarmouth and Boston. He died in 1832 when his ship Messenger, which had gone aground on a sand bar in Yarmouth Harbor, rolled over and crushed him. Captain Oliver Hallet later occupied this house. He was known for helping to plant in 1843, along with Amos Otis and Edward Thacher, the many elm trees that once lined OKH.

Yarmouth’s elm trees along Old King’s Highway.

The creek from Mill Pond was much wider and deeper then, with wharves that allowed vessels the size of brigs to load and unload their passengers and cargo. Yarmouth had several packets that sailed in and out with regular trips to Boston. However, when the railroad came through, the packet ships were unable to compete and ceased service in 1871.

A dam was built in 1889, at the cost of $61.50, to control the flow of the tidal waters. In 1898 the Portland Gale partially destroyed the bridge which was rebuilt. During a storm on Dec. 26, 1909, the tide washed over Mill Lane to a depth of 15 inches and broke completely over the railing of the bridge at Mill Pond. A portion of Thacher Shore Road was also submerged.

Carrie & Mary Park have their photo taken by the bridge in the late 1890s.

During the 1900s the Lovells, a fishing family from Barnstable, built a fishing shack/boat house along the creek next to the bridge.

Today Yarmouth residents enjoy fishing off the bridge, swimming in the creek and taking in the beautiful views. It is still a very appreciated part of Yarmouth Port.

Herbert Lovell’s fishing shack on Mill Creek.

Excerpted from an article by Pat Tafra.