With the fall of Fort Sumter in April, 1861, Cape Codders rallied around the Union and responded with an enthusiasm unequalled in any previous war. Sandwich immediately sent a militia regiment to fight and other Cape towns offered native sons for the initial 90 day enlistment of 75,000 troops requested by President Lincoln. Local women mobilized to form Soldier’s Relief Societies. Women gathered together to make items that the soldiers would need such as havelocks, hand-knit socks and mittens, towels, sheets, pillowcases, shirts and warm quilts. They “picked lint” to provide soldiers with dressings for their wounds and rolled bandages for use at field hospitals. The men of the town, meanwhile, raised money to help support the families of the men who had gone to war and, eventually, to offer bounties to encourage enlistment.

Yarmouth women, 1860s.

Many of Yarmouth’s sea captains were out to sea as hostilities broke out at home. The meager Confederate Navy, seemingly no match for the great maritime strength of the Union, wrought havoc with merchant shipping. The raiders captured commercial vessels and ransomed them for bounties or burned any ship carrying cargoes that might in any way be connected to the war effort. The piracy of the Confederates brought a great slow-down in merchant shipping. Some captains carried on, finding great excitement in the cat and mouse game. Others, like Captain Bangs Hallet, retired in the midst of the war, no longer willing to endure the risks. Marine insurance rates soared. Ship owners began to sell off their vessels in an attempt to protect their assets.

Captain Oliver Thacher

Other Yarmouth men also depended upon the sea for a living: the fishermen. Dozens upon dozens of small fishing schooners, harboring in

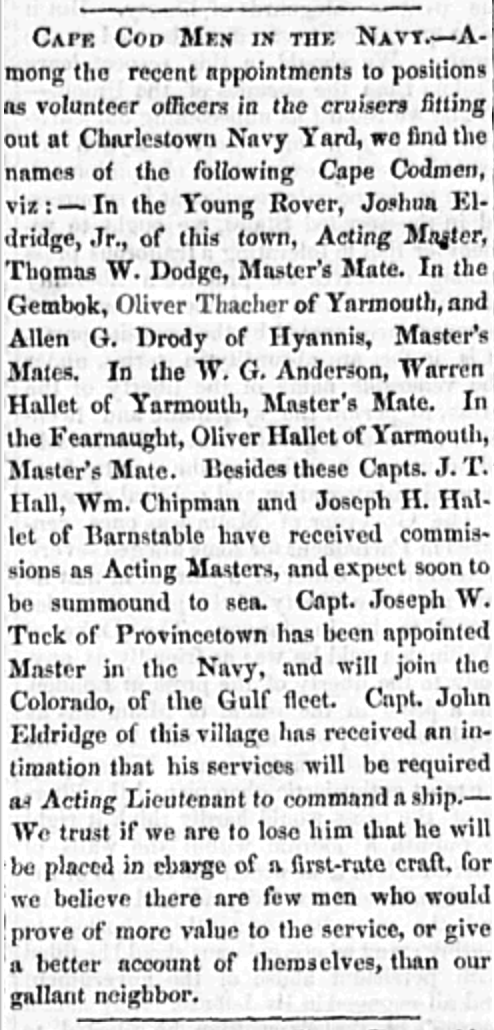

Yarmouth Register, 1861

Lewis Bay, Bass River and Yarmouth harbor, found their markets for fish completely cut off. Their last catches lay rotting along the banks while their ships remained idle. With no fish to preserve there was less need for salt, another major product Yarmouth citizens harvested from the sea. By the end of the war, the fishermen’s boats had lain so long in disuse that to begin again meant building new ships. Many abandoned the sea, and the Cape, for careers inland. Salt works were dismantled and the rot-resistant wood used to build barns and outbuildings.

Throughout the course of the war, Yarmouth offered its sons to the Union Army and others to the Union Navy while many more served as pilots for Navy ships in Southern waters. [See note at end] Perhaps the biggest enlistment to the cause came in the fall of 1862 when Lincoln sent out a call for more men as it became clear that the war was not going to end as quickly as everyone had hoped. Edwin Hale Lincoln, the son of Yarmouth’s Unitarian minister and a distant relative of President Abraham Lincoln, begged his father to let him enlist as a drummer boy. Although barely 14, Lincoln wanted the excitement and adventure of the war and argued that his cousin would be there to protect him. Jarius Lincoln, Edwin’s cousin and the principal of Yarmouth’s grammar school, enlisted in the Fifth Massachusetts Regiment. A fellow school teacher, Daniel Wing, joined him. Wing was a Quaker, a member of the Yarmouth Meeting in Friend’s Village (South Yarmouth). Although the Quakers were against the use of violence, they very much believed in the equality of all people, and were leaders in the anti-slavery movement. Perhaps this is why young Daniel choose to go to war, or perhaps it was in search of his own adventure. Many other young men of the town enlisted in the late summer and early fall of 1862, assigned not only to the 5th Regiment, but also to the 40th Massachusetts and various other units. For most of them, the term of enlistment was to be nine months.

Edwin Hale Lincoln in uniform.

Daniel Wing

Yarmouth’s, and the Cape’s, most decorated soldier was Joseph Hamblin. Hamblin, who lived on Summer Street in Yarmouth Port, moved to New York as an adult and enlisted with one of the first regiments to be mustered into the Army of the Potomac: the Fifth New York. Hamblin was named the Adjutant for this colorful group of Zouave soldiers and quickly distinguished himself. The soldiers of the 5th looked to Hamblin as a brave and heroic figure. One of the soldiers of that regiment wrote, “In bodily formation this man, chiseled in marble, would have rivaled the Apollo Belvedere. He was one of nature’s masterpieces and the finest I ever saw. By his many engaging qualities he won the affection of the men; they loved, honored, almost idolized him.” In 1862 Hamblin was promoted to Lieutenant Colonel of the 1st United States Chasseurs. Hamblin participated in nearly every major battle fought by the Army of the Potomac, from the first battle at Great Bethel in June of 1861, to the very last battle at Sayler‘s Creek in April of 1865. At Cedar Creek he was wounded twice, but refused to leave the field until the battle was assuredly won. After a brief recuperation in Yarmouth Port, Hamblin returned to duty not having missed any major action. His unit was the last one mustered out of the Army in 1865 and Hamblin left the War at the rank of Brevet Major-General. Hamblin died an early death in 1870, having succumbed to “diseases contracted during the War of the Rebellion.”

Brevet Major-General Joseph Hamblin

In April of 1865, bells rang from the Methodist church in Friend’s Village, the Congregational Church on Yarmouth’s common, the Universalist Church in Yarmouth Port and the Congregational Church in West Yarmouth. The war was over. But days later, the bells rang once more as Yarmouth learned that President Lincoln had been killed.

The Civil War, although carried out far away from the isolated shores of Cape Cod, left its mark on the town of Yarmouth and its citizens. For soldiers like Daniel Wing and Edwin Hale Lincoln, it provided an adventure never to be forgotten and an experience that shaped their lives. For the women of Yarmouth’s villages, the war created an outlet for their talents, an opportunity to be part of a cause. But for all those associated with the maritime economy of the Cape, the Civil War “stood squarely between the good times and the bad.” Although the decline of American merchant shipping had imperceptibly begun prior to the war, the war hastened the end of an era and forced Cape Codders ashore. The glory days of Yarmouth’s deep-water captains, the prosperity of a community supported by the products of the sea -- all were gone. Some moved inland; clipper ship captains retired; fishermen became tradesmen and merchants; and the population of Cape Cod towns began to decline. In the words of historian Henry Kittredge, “No community that depends on the sea for its prosperity can flourish long after it is driven from the sea ... the war got the blame.”

*Note – Author Charles Swift mentions 250 men served from Yarmouth. That’s 10% of the total population of the time. Cape Cod and the Civil War: The Raised Right Arm, by Stauffer Miller, 2011, is a book on Cape Cod and the Civil War. He says about 1,000 men served from Barnstable County, and several hundred in the Navy. If 1,200 served then that would be 80 or so men from each town on the Cape. It’s had to know how many served. Soldiers and Sailors of the Civil War lists only 60 names from Yarmouth.

Written and researched by Barbara Milligan Ryan

Brevet Major-General Joseph Hamblin, left.