No US President visited Cape Cod prior to the Civil War. Was it because of the terrible press that Cape Cod had endured? Before the war, the Cape was mocked both for its scenery and its people. Author Nathaniel Willis wrote that Cape Cod was “the earth’s most unattractive region.” Others said there were so few trees that Cape Codders used fog for shade. Herman Melville in Moby Dick, used chapter 14 to disparage Nantucket. He even went so far as to say that Nantucket had so few things that grew that they even had to import weeds. An 1863 children’s book said Cape Cod’s landscape was a symbol of emotional deprivation.

Cape people also were attacked. John Werner said that Cape seamen as a class were more addicted to vice than many others. Nathaniel Willis bemoaned the fact that Cape women were not shapely, and even Ralph Waldo Emerson noted that Chatham opposed lighthouses as they hurt the salvage wrecking business (untrue!). Thoreau frequently disparaged the mid-Cape people.

In view of this, it’s easy to see why people wouldn’t visit. Of course, it also may have been that the railroad didn’t cover the entire Cape until after the Civil War and there was less available steamboat transportation until then.

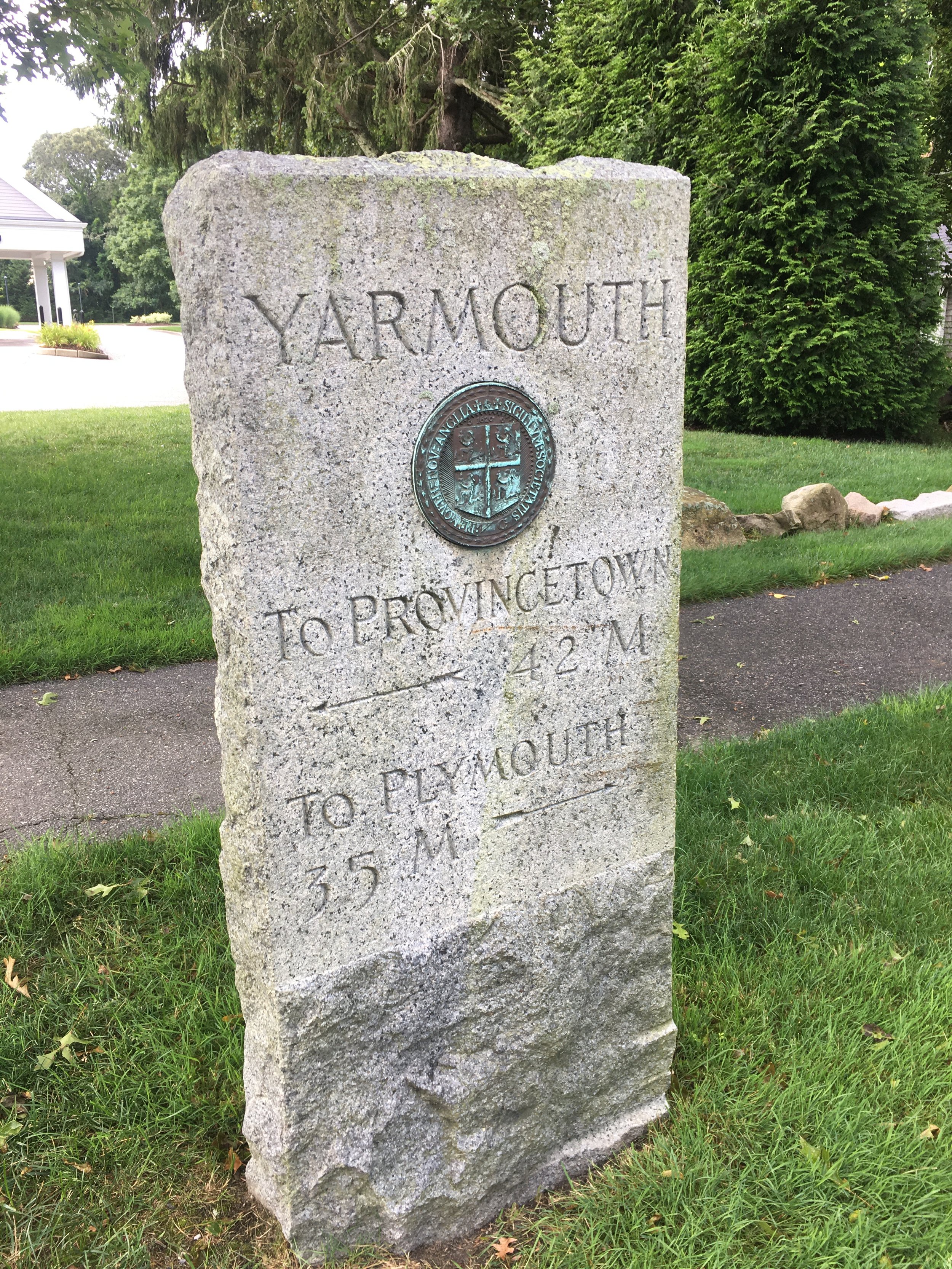

In any case, the first President to visit us was Ulysses S. Grant. In August 1874, Grant and his entourage arrived on Martha’s Vineyard. The next day they steamed to Hyannis where they rode a train through Yarmouth to Provincetown. They later returned by train to Sandwich, then to Woods Hole and back to Martha’s Vineyard. Grant was the first to make the Cape a vacation destination. Grant’s wife Julia was treated kindly by the Cape press, never mentioning that she had strabismus, a condition that made her cross-eyed.

Grant visiting Martha’s Vineyard in 1874.

President Chester Arthur was on Nantucket in 1882 for a lunch, being the second to visit. President Grover Cleveland made Cape Cod his summer home. He purchased Gray Gables in Bourne in 1890 (it burned down in 1973). It was his summer white house during his second term in office. Cleveland loved to fish. Charles Cory had developed West Yarmouth’s Great Island both for game and for fishing, and he stocked the ponds with trout and other game fish. To ensure sufficient water flowing through them, he built an underground piping system with water pumped by windmills. President Cleveland visited Cory and for four days the two fished the ponds where Cleveland caught a three pound trout.

Cleveland’s Gray Gables.

Aside from President Kennedy, Cleveland is probably the best known president on Cape Cod and stayed more time in Yarmouth than any president. In between Cleveland’s two separated terms as president, President Benjamin Harrison paid a brief visit to Nantucket.

It was Teddy Roosevelt who next came to Cape Cod. His first visit was only into the waters of Cape Cod Bay near Barnstable where he watched, from the deck of a battleship, the US Navy take part in target practice with big 12 inch guns, rattling windows all along the bay. Provincetown was a major naval base during this time.

Teddy didn’t come ashore during this review, but in 1907 he did attend the laying of the cornerstone of the Pilgrim Monument and gave the main address. He had sailed into Provincetown harbor that day on the presidential yacht Mayflower, accompanied by his wife, son, and daughter. The entourage took two carriages to the monument. Three years later, President William Howard Taft came to Provincetown to celebrate the monument’s completion.

Theodore Roosevelt at the 1907 Pilgrim Monument cornerstone ceremony.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt didn’t become president until 1932, but he visited Cape Cod 18 years earlier. Roosevelt, as Undersecretary of the Navy, was aboard the destroyer McDougall during the parade of ships through the Cape Cod Canal when it opened in 1914. Later, in 1933 while president, he was supposed to visit Provincetown aboard his yacht Amberjack II, but poor weather made him by-pass Provincetown on his way to Gloucester.

FDR was on hand for the opening of the Cape Cod Canal in 1914.

The next visitor was President Woodrow Wilson, who in 1917 went to Nantucket on a private visit to see his daughter.

There is a question as to whether President Calvin Coolidge visited Cape Cod looking for perfect clams. However, it appears that two Cape Codders took those clams to Washington and he ate them there.

George H. W. Bush

George H. W. Bush first visited the Cape as a Navy pilot during World War II. He was stationed at the airport in Hyannis where he perfected his take-offs and landings on a simulated carrier strip at that airport. It was the only night lighted civilian airport on Cape Cod before World War II, and during the war was a very busy training facility. It operated three 4,000 foot paved runways, built by WPA workers. President Bush also visited Mashpee in 1990 and in 2005 visited Martha’s Vineyard.

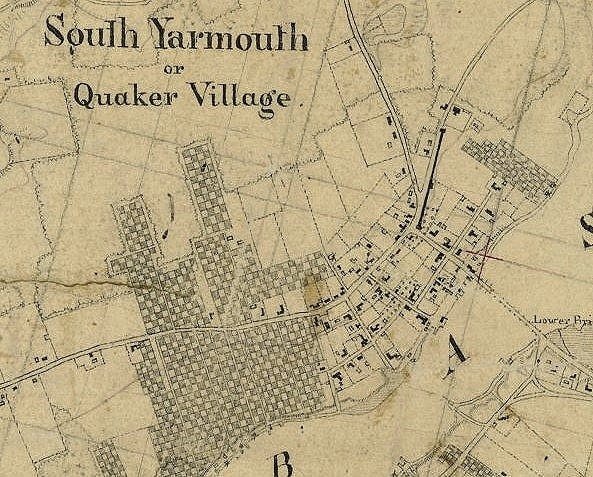

Before being elected president, General Dwight Eisenhower, visited General Lucius Clay in Dennis on Wrinkle Point. The two swam across Bass River to the a dock belonging to Sally Parker. Not recognizing them, she told them to leave, they were on private property. Word went around that Ike could cross the English Channel and invade Europe, but couldn’t secure a landing in South Yarmouth! In 1957, there were rumors that Ike was going to celebrate the 4th of July in Osterville. Did he? This writer never found out.

The next visited Cape Cod in 1950, more than 20 years before he became President. Jimmy Carter was stationed in the Navy in Provincetown for a year. Wife Rosalyn recalled their time there in her memoir – First Lady From Plains. “We rented an upstairs apartment in a big old house, and there the children and I could sit at the breakfast room table and watch the submarines operate and dive just off shore. ... And we bought the boys their first sleds even though they had to compete with us to use them.” Apparently the Carters didn’t know the Cape ditty – “Cape Cod boys they have no sleds; they slide down dunes on codfish heads.”

Jimmy Carter on board a submarine.

We all know John Kennedy’s attachment to Cape Cod and his lifelong love of sailing the waters around the Cape. He also played a crucial role in creating the Cape Cod National Seashore. Plan a visit to the Kennedy Museum in Hyannis to get a full account of his life and times on the Cape.

President Bill Clinton made four trips to Martha’s Vineyard during his presidency, landing at Otis Air Base and then transferring to the island.

The Obamas spent several vacations on Martha’s Vineyard while he was President, again landing first at Otis. Cape newspapers reported almost every sighting of him, every time he came.

Donald Trump visited the Cape as a candidate in August of 2016, stopping on Nantucket and then in Osterville. There is no record of any tweets that he might have made.

President Joe Biden has visited Nantucket every Thanksgiving since 1975.

Adding it up, nearly two-thirds of US Presidents have visited Cape Cod and/or the islands since 1870. Only two have missed us in the last 40 years. Their loss!

Researched and written by Duncan Oliver

Presidential yacht Mayflower at Marblehead, 1925.