The war which America had declared on Britain in 1812 grew harder on Yarmouth and other Cape Cod towns in 1814.

In the beginning, the war on this side of the Atlantic was just a tiresome irritant for Britain which was focused on the ongoing threat from Napoleon. That changed in the spring of 1814 when Napoleon suffered losses and was forced into a temporary abdication. This allowed the British to swing more of their forces against the upstart Americans.

Our country’s own embargo on shipping and the early British blockade of American ports had already drained much of the Cape’s economy. Now, as the summer months of 1814 approached, so did more British ships.

As their blockade tightened around the Cape it strangled our maritime trade. Cape Codders couldn’t export goods for sale nor could they import much of what they needed. Slow, laborious land routes connecting the Cape with the rest of war-beleaguered America just couldn’t meet our growing needs. Without the shipping trade there were fewer jobs, less money and less to eat.

click to enlarge

Threats to the mid-Cape towns became more severe. The British were picking off vessels that dared venture out. They had attempted landings in some places and started making ransom demands on saltworks, buildings and boats in Yarmouth, Barnstable and Brewster. Falmouth was shelled and there was fighting in Orleans. These were dangerous times.

The more dangerous the British threat became, the more willing Yarmouth was to resist. Benjamin Hallett, born in 1810, told his grandson that the earliest memory of his life was of being carried in his mother's arms down through the streets of Yarmouth to a place of safety one bright moonlit night in 1814, and seeing the local militia coming up from down Cape and seeing the moonlight flash upon their bayonets as they marched to Barnstable to repulse an expected landing of British from a frigate in the harbor. The H.M.S. Spenser, commanded by Captain Raggett, had demanded Barnstable village pay a ransom of $6,000 or local saltworks would be destroyed. Cannons (now in front of the Barnstable courthouse) were pointed toward the ship and they left empty handed.

British frigates operated from Provincetown harbor. From there they could patrol Massachusetts Bay in their sometimes unsuccessful attempt to keep the troublesome USS Constitution bottled up in Boston. And from Provincetown they could patrol to the south, hunting down American shipping in Nantucket Sound.

The USS Constitution in 1803.

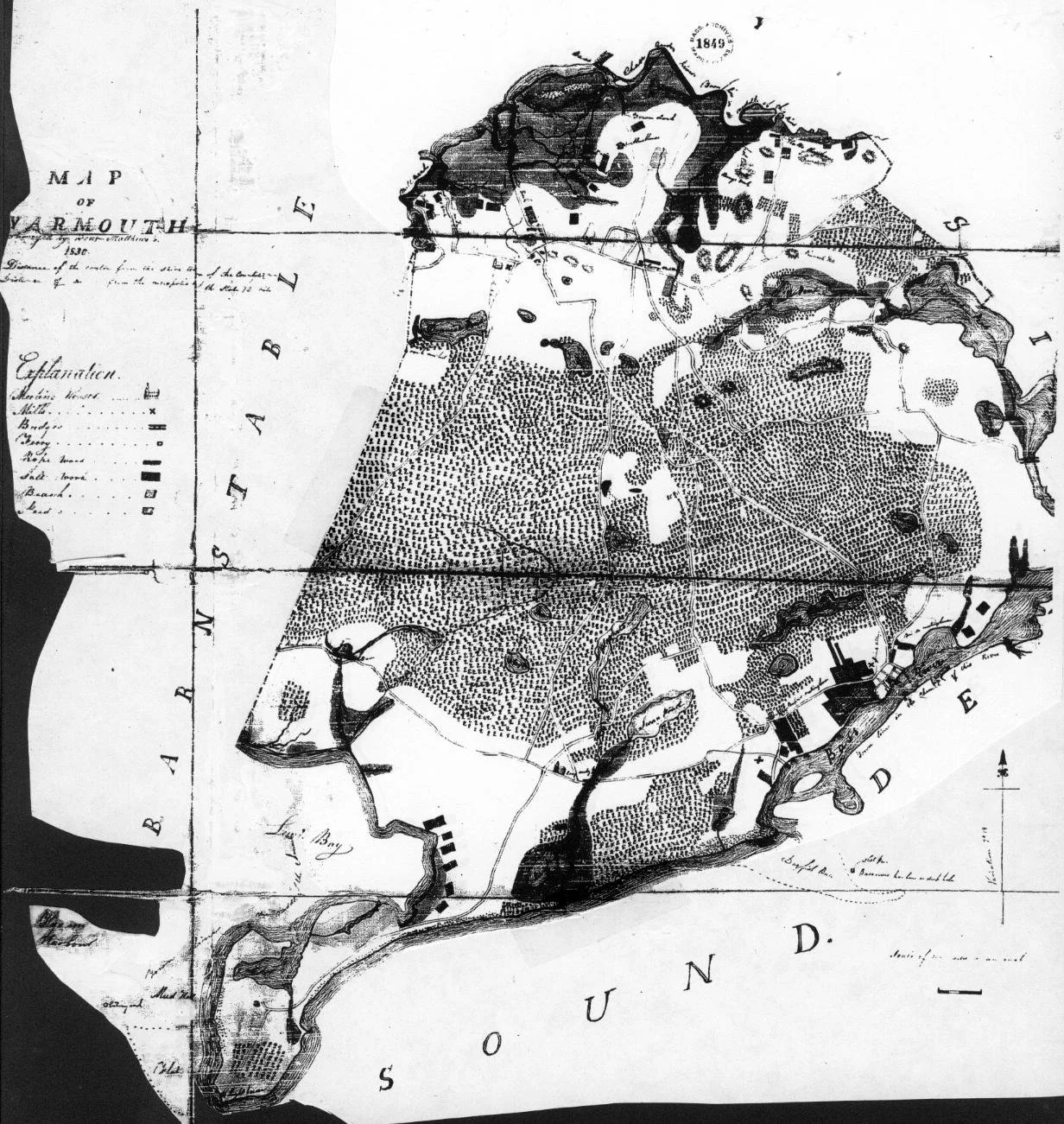

Yarmouth’s Bass River, with its fleet of fishing boats, was on their watch list. So, too, was Lewis Bay, nestled between Yarmouth and Hyannis, because sheltered in the bay was Hyannis Harbor, a snug, protected place of refuge for any ships that could thread their way through the blockade.

A key part of the harbor complex was Gage’s Wharf. It jutted into the bay from Yarmouth, just east of the Hyannis line, along what we now call Bay View Beach. It was just what larger blockade runners needed for quick unloading. To protect the wharf, militiamen built chest-high breastworks in Yarmouth just east of Bay View Beach, in the area now known to us as Hyannis Park. Just across the water more breastworks were dug along Fish Hills, an elevated vantage point overlooking the wharf and inner harbor entrance on the Hyannis side of the line.

A view of Hyannis Park in the early 1900s.

There were fortifications on Yarmouth’s Great Island to protect the east side of Lewis Bay, where the channel runs in from Nantucket Sound. We know from early records that there were ammunition pits on Great Island, and more breastworks. Coastal watches were kept and militiamen from West Yarmouth drilled there in preparation for repelling any attempted invasion.

A fort had been built to guard Lewis Bay as well. It was named Fort Masonic, almost surely like other similarly named forts along the East Coast, because it had been built by members of the Masonic order. We are not certain of the location but because of the ammunition pits known to be on Great Island, it is likely the fort was there as well.

Some of what we do know comes from an application for bounty land for service in the War of 1812 filed in 1857 by Joseph Linnell of Yarmouth. His application included corroboration from two other militiamen who stated “...we knew him when he belonged to Yarmouth and to the Company of militia commanded by Elnathan Lewis; and that he was employed with ourselves during ... 1814 ... in building Fort Masonic at Lewis Bay and Breast Works on the Fish Hills and to stand guard at the above places and at Hyannis Port ...”

The British may have ruled the sea but Cape Codders controlled the land and were ready to resist any landing attempts. The British used shallow-draft barges when approaching shore. Their large ships drew too much water, so smaller, nimbler craft were needed. The breastworks and other defenses around the bay were adequate to deal with these smaller craft.

An 1830 map of Yarmouth, including Great Island at the bottom.

The British did strike ashore at least once from Lewis Bay. That was in June of 1814 when the United States brig Kutuzoff, under pursuit and being shot at by a British ship, was beached on the Hyannis side of Lewis Bay by her captain, Sylvanus Alexander of Hyannisport. In their attempt to destroy the brig, the British sent in a landing party and hoped to burn it.

By the time they were ready to land, however, the militia had responded, reportedly with as many as 100 men and a cannon, and the British were driven off and back to their ship.

Still, the attempt by the British to come ashore was alarming to the Lewis Bay defenders and something they didn’t want happening again. Isaiah L. Green, who had once represented the district in Congress, wrote to the American army general in Boston asking for help in meeting any further British attacks.

“We have no artillery and our militia are not armed and equipped as they ought to be.” he wrote. He requested “a small detachment” and “flying artillery would be the most eligible kind of force.” Flying artillery meant cannon mounted on wheeled gun carriages. They could be moved from point to point as danger presented itself whereas cannons in a fixed position might be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Flying artillery cannon.

There is no evidence we could find that the state supplied help in any form during the summer of 1814, but the war was starting to wind down. Both sides were looking for ways to end it; peace talks were initiated and winter further chilled the ebbing conflict. Peace came with the Treaty of Ghent, signed on Christmas Eve 1814. News travelled slowly in those days, however, and it was 1815 before most Cape Codders knew it. They were very grateful.

Researched and written by Dick LeGrand